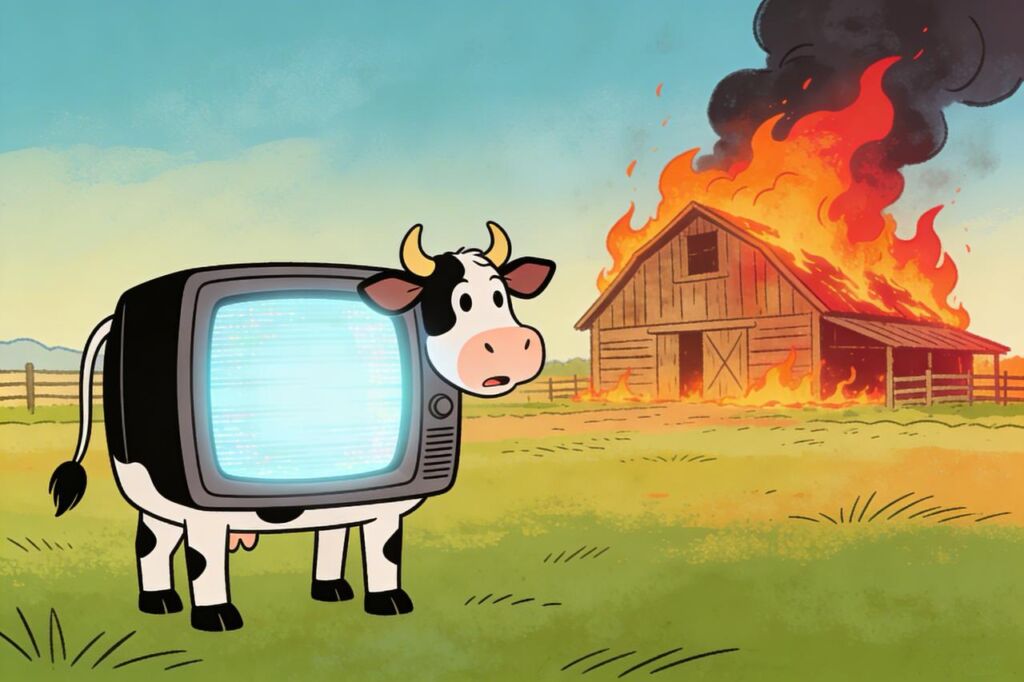

Is CTV Really Advertising's Premium Pasture?

by Shirley Marschall on 18th Feb 2026 in News

Shirley Marschall is back - this week she's looking at why CTV reminds her of a joke about a cow...

Here’s a story about Kuh Elsa: A butler informs his employer, the Count, that one of his cows has died. The Count owns more than 3,000 of them, so he barely reacts. Unfortunate, he says, but hardly catastrophic. Cows die. That is, after all, what cows do. Still, he asks how it happened.

The roof of the barn fell on her head.

Why did the roof fall? Because the barn burned down.

Why did the barn burn? Sparks flew from the manor house.

Why was the manor on fire? Because the Count’s son fell down the stairs and broke both arms while carrying a candle, trying to create a nice atmosphere for the Countess.

And why was he doing that? Because the Countess had died unexpectedly.

By the time the explanation is complete, the cow feels almost beside the point. What looked like a single, unfortunate incident turns out to be the last visible consequence of something that started much earlier and much higher up.

Connected TV has a faint Cow Elsa quality to it.

CTV is being sold as the premium pasture of digital advertising. The big screen in the living room. Lean-back viewing. Higher attention. Brand-safe adjacency. TV budgets migrating into streaming environments that promise the efficiency of digital with the gravitas of broadcast. It sounds tidy, almost redemptive. As if digital advertising, after years of chaos, has finally found a setting worthy of itself.

But once you start asking a few quiet "why" questions, the edges stop looking quite so clean.

"CTV underperformed."

Why? Because impressions were misclassified.

Why were they misclassified? Because device and app signals in the bidstream are often self-declared, inconsistently validated, or interpreted generously.

And why is that even possible? Because the plumbing was built to prioritise liquidity. OpenRTB was designed to let inventory move. Flexibility makes markets fluid, fluid markets scale, and scale, right now, is the whole point.

There is nothing particularly dramatic about that. It’s simply how the system was designed. And systems tend to behave the way they are incentivised to.

Which is how you end up with inventory masquerading as CTV. As Will Rand, co-founder of CleanTap.ai, put it recently: "Right now, a huge % of ad space on sale as CTV is actually TV/out-of-home or DOOH masquerading as CTV. This is because of grey areas in labelling and the IAB’s OpenRTB spec. In 2026, many of these grey areas will face a correction. All companies, meaning buyers, sellers, and legitimate DOOH operators, will benefit from this clarity." The language is blunt, but the broader point is very familiar. Stretch definitions and behaviour will stretch with them.

Yes, CTV has expanded incredibly fast. FAST channels have multiplied into the thousands, offering everything from hyper-niche content to recycled libraries that feel reassuringly linear. The terminology alone can trip people up. CTV refers to the device, FAST is a content model, and OTT describes delivery. And that is before the industry resumes its never-ending debate about whether YouTube counts as CTV.

In theory, those distinctions may matter. In practice, they blur. And in many buying conversations, they blur completely. The knowledge gap is real, and the opportunism around it grows fast. After all, CTV sells, and why clear the air about terminology if it risks ruining a deal?

Anyway, behind the screen, the mechanics are recognisably programmatic. Inventory is bundled, resold, optimised, packaged, and repackaged. On top of that familiar infrastructure, increasingly ambitious promises are being layered. AI-driven optimisation. Self-serve access. Retail data overlays. Cross-screen frequency control. Advanced attribution frameworks. And the list goes on…

But then there is a signal problem, another "why" to trip over. A recent report suggests that a meaningful share of programmatic CTV spend may not reach the households advertisers think they are targeting. Not because of spectacular botnets necessarily, but because the identity signals underpinning open programmatic buying are inherently probabilistic.

As Scott McKinley, CEO of Truthset, observed: "In order to assign an audience attribute to a connected television device, you have to go through three or four match processes in the data supply chain, each of which introduces probably a minimum of 50% error."

Three or four match processes, each introducing an error… so by the time an audience segment appears neatly attached to a device ID, it has already travelled through layers of matching, inference, and assumption. But then again, when did targeting ever really work the way we like to believe it does?

None of these problems, and there are certainly others, makes CTV uniquely broken. It simply looks like what happens when familiar programmatic mechanics are asked to behave like TV while scaling at speed, under pressure, with budgets flowing in faster than definitions and guardrails can catch up. Meanwhile, CPMs retain the aura of "premium," because the screen is (ideally) big and the setting feels different.

Which brings us back to Kuh Elsa. Next time, before celebrating the size of the herd and the promise of premium, it might be worth asking a few more "why" questions about the structure holding it together.

Shirley Marschall is ExchangeWire's weekly columnist - find her on LinkedIn where she's making sense of ad tech.

Follow ExchangeWire