Publishers Let Randoms Stick Ads In Their Slots

by Mathew Broughton on 9th Mar 2020 in News

In his latest article penned for ExchangeWire, Independent Ad Fraud Researcher Dr. Augustine Fou (pictured below) discusses the risk publishers face by allowing third-party vendors to serve ads into slots on their sites.

Would you let someone stick their germ-ridden, muddy fingers in your cookie dough, right before you eat it? Ew, of course not. But that is exactly what publishers are allowing to be done to them by allowing ads from programmatic sources to be served into ad slots on their sites and allowing “content discovery” and “promoted content” widgets to pipe “chumbox” content into their pages.

Many have warned against the security risks of allowing third party javascript on publishers’ pages (for example: [I], [II], and [III]). But this week brings fresh examples that illustrate the problems well. GeoEdge captured screenshots of ads being served into major publishers’ sites by scammers selling “n95 masks” and spreading fake news and disinformation about coronavirus.

The key point is that the site owners with ad slots that accept ads from programmatic sources do not know ahead of time who will be sending ads into those slots and what ads are going to be displayed, until the ad gets displayed. Scammers use every feature of ad tech in order to send ads into those sites, for example, users who visited pages about “Covid-19” (behavioural targeting), users who searched for such news (search retargeting), and pages that have content related to the coronavirus (contextual targeting). This is the exact same phenomenon as malvertising, where ads laced with malicious code are deliberately served into mainstream sites with real human audiences, targeting their real devices for compromise (hackers don’t need to compromise bots).

But consider the following problem that cannot be solved by technology, letting some outside vendor decide what ads can or cannot run on your pages, i.e. whether you can monetise your content or not. Ad tech maven Ari Paparo captured a telling screenshot of the front page of New York Times’ website showing an ad with white clouds in it.

Anyone recognise that? It is the default ad that fraud verification vendor DoubleVerify serves up when they determine a user is invalid (IVT - invalid traffic) or the page is not brand-safe. That’s right, a third party vendor gets to decide whether an ad can run or not on a major publisher’s website. Would you let someone else determine whether you can make money or not from your own webpage? I surely hope not. But that’s exactly what is happening.

Dr Augustine Fou, Independent Ad Fraud Researcher

The problem is that the fraud verification and brand safety vendors are black box, that means they deliver the verdict of fraudulent but don't or can't explain HOW they marked something as fraudulent. They say this is because they have to keep their "secret sauce" secret. But yet, they are given the power to determine if a publisher can monetise their own content or not. We have seen many examples of false positives (publisher bring accused of IVT when there was none) or a page being marked as not brand safe when it actually was fine, for instance the article about the Duchess of Sus(sex). There are now dozens of articles showing that real news sites’ ad revenues are hurt by brand safety tech vendors, while fake news and disinfo sites continue making money and proliferating. Further, in many cases the advertiser has already paid for the impression (that was replaced by the cloud ad) but the publisher is left to defend themselves against IVT and brand safety accusations, without being presented with evidence so they can see what they need to do to fix it.

A related problem is when malvertising is served into the site, users are redirected away to scam sweepstakes or tech-support sites. The rest of the ads on the publishers’ page suffer because the hijacked user is no longer even on the publisher’s site and has no opportunity to click on the other ads. Further, the user who got hijacked thinks that the publisher did that to them, or did not do enough to protect them from being hijacked. So there is reputational harm for the publisher when random ads from programmatic sources get served into their slots.

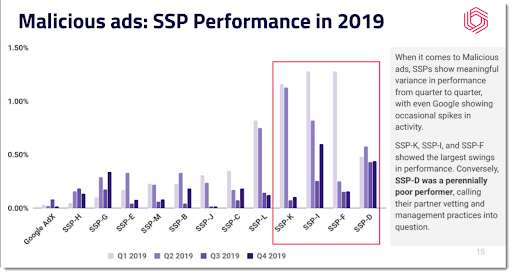

So what can publishers do to minimise these risks and harms? Some site owners have deployed services like Confiant, GeoEdge, and Clean.io to scan every ad for malicious code. But scammy or misleading ad creatives may still get by this technology. If a publisher decides to continue to let ads from unknown programmatic sources be served into their ad slots, they should at the very least ban the worst SSPs (supply-side platforms). Confiant has shown over many studies that a small handful of SSPs account for the majority of the bad ads; ban those. Finally, sell more “direct.” By selling to reputable advertisers and reserving ad slots for their ads, publishers can reduce the number of bad ads served in by “randoms,” and simultaneously reduce the false accusations and monetisation blocking by third-party verification firms used to detect IVT and brand safety violations.

Ad FraudAd VerificationBrand Safety

Follow ExchangeWire